Last year, shortly after becoming the Port of Tacoma’s executive director, Eric Johnson marched into the offices of Port tenant Art Morrison Enterprises. He was a man on a mission.

Workers in Morrison’s outer office called after the man in the suit, but Johnson didn’t stop until he was face to face with the famous classic car chassis designer.

Workers in Morrison’s outer office called after the man in the suit, but Johnson didn’t stop until he was face to face with the famous classic car chassis designer.

“I said, ‘Are you Art Morrison?’” Johnson said, his voice cracking even months later as he recounted the meeting. “’You don’t know me, but I used to worry about you.’”

A smile spread across Morrison’s face. The smile is a Morrison trademark, a byproduct of his perpetual optimism. Johnson knew the smile; he’d seen it more than 50 years earlier.

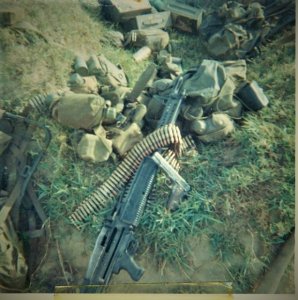

In 1967, Johnson was a third grader growing up in Fife and his teacher, Velma Morrison, kept a picture of her son on her desk. In the image, Art, a machine gunner serving in the Vietnam War, wore his M1 helmet, his dark green fatigues and he was weighed down by gear and ammunition. He held a half-smoked cigarette in his right hand and smiled broadly.

The picture was taken as Morrison’s unit returned from a combat assault on a coastal village. They didn’t find anything, and nobody was injured. “It was a good day,” Morrison said.

The picture of the young soldier captured Johnson’s imagination as a child. At home he watched coverage of the Vietnam War and asked his dad questions. Could Mrs. Morrison’s son get hurt? Could he die?

The truth was sobering. Frequently Johnson asked Mrs. Morrison about her son and Mrs. Morrison said her son was doing fine.

In reality, Morrison’s year in Vietnam was harrowing. People he knew died. He was injured by a grenade in a friendly fire incident. And an infection from a leach bite left him dangerously ill.

In reality, Morrison’s year in Vietnam was harrowing. People he knew died. He was injured by a grenade in a friendly fire incident. And an infection from a leach bite left him dangerously ill.

Still, Morrison considers himself “unbelievably fortunate.” His tour ended in January 1968, less than a week before the Tet Offensive, which resulted in heavy casualties on both sides.

When he came home Morrison didn’t hear much about people like Johnson who worried about his safety and admired his heroism. It would be more than 40 years before President Barack Obama declared March 29 National Vietnam War Veterans Day. Instead, Morrison was warned not to wear his uniform in public because many civilians took out their hatred for the war on the troops.

Morrison didn’t let the negative climate derail his future. He briefly attended Tacoma Community College before realizing college wasn’t his thing. He drove a wheel stander — a wheelie-popping dragster — before a nasty crash led him and his wife, Jeanette, to realize “there must be a better way to make a living.”

He grew up building houses with his father, Bob, and had an inherent talent for creating. A friend, recruiting him for his welding skills, asked him to help restore a Corvette. When the car had a record performance, Morrison started working on other projects.

He’s been in demand ever since. Today, Art Morrison Enterprises, which turns 50 next year, is a world-renowned source for finely crafted chassis components used to remodel hot rods and classic cars. AME is housed in five buildings (about 42,000 square feet) at the Port. “Anybody who restores cars knows the name Art Morrison,” Johnson said.

Even if they haven’t admired him for as long as Johnson.

“It’s great to have a company like that thriving at the Port,” Johnson said. “It is cool.”

Photos courtesy of Art Morrison.